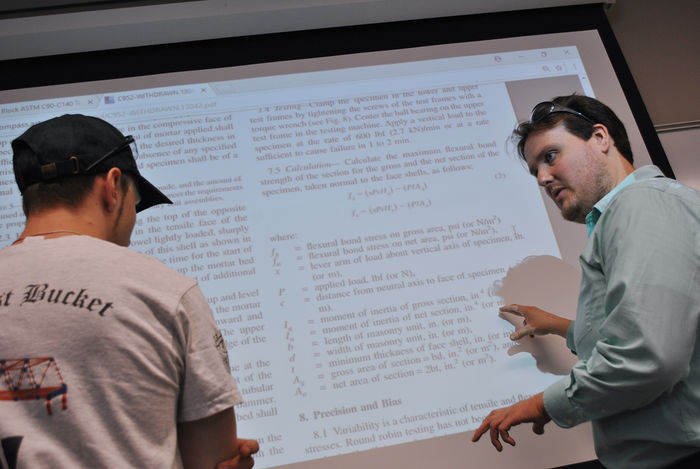

Grady Mathews, assistant professor of civil engineering at Penn State Harrisburg, and his students are testing new ways to use incinerator waste as a replacement for sand in concrete.

MIDDLETOWN, Pa. — Trash incinerators produce massive amounts of ash, which ends up in landfills. In the United States, available land space for landfills is decreasing, and the construction industry is looking for ways to utilize more sustainable materials.

Grady Mathews, assistant professor of civil engineering in the Penn State Harrisburg School of Science, Engineering, and Technology, and his students are testing a process that could provide solutions to both problems.

Mathews believes that after some refinement, ash from waste can be used as a partial replacement for sand in cement-based construction materials, like concrete. Sustainability initiatives and available subsidies to offset landfill disposal costs provide a significant incentive to use the ash this way, he said.

“It costs $30 to $40 a ton to send ash to a landfill,” Mathews said. “An incinerator plant would make a profit if someone would haul it away for free,” and, presumably, put it to good use.

According to Mathews, although using ash in construction materials has been studied before, no one has developed a wide-scale process to refine the ash into a product that meets environmental and structural requirements. Ash from solid waste contains large amounts of heavy metals, salts, and organics that must be filtered out before the material can be used.

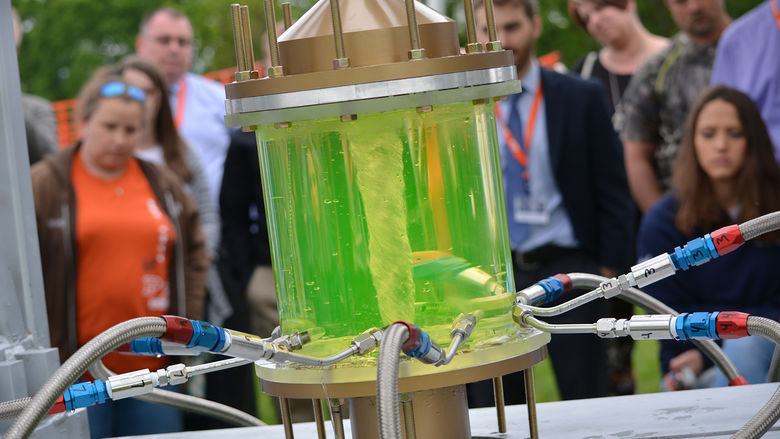

Mathews is working with Pure Recovery Group, a Toronto-based company with offices in York, Pennsylvania, which had developed a Department of Environmental Protection-approved recycling process to refine the ash, with the resulting product known as reclaimed sands.

Pure Recovery Group Chief Operating Officer Jay Berman said the company has been working to perfect the system, which already meets the specifications for making masonry block. A demonstration plant at Standard Concrete in York is manufacturing the block to show it can be done commercially.

Pure Recovery Group processes ash from the York County Solid Waste Authority incinerator plant.

“We could have the first plant up and running by the end of the year,” Berman said.

Dave Vollero, executive director of the waste authority, said he is excited about the potential.

“We've been working on this for a long time,” he said. “It saves landfill space and has a compounding benefit. It will make waste-to-energy more attractive, and saves greenhouse gas emissions compared to landfills. It's an environmental plus all around as well as an economic plus.”

By recycling the ash instead of disposing of it, the waste authority can reduce operating costs, with savings passed on to customers, he said.

According to Mathews, Penn State Harrisburg's tests show that masonry block made with reclaimed sands meets required international material standards specifications. The masonry blocks have the required strength to be used in construction and are lighter than traditional blocks. Mathews and his students continue to test the product’s performance.

Vollero said it could still be a while before the masonry blocks are widely sold, but many municipalities have already shown interest.

“We need to make them on a regular basis and consistently,” he said, before they can go to market.

The Pure Recovery Group is working on other ways to use the ash aggregate in concrete, Berman said.

“We're working with Penn State Harrisburg to prove that the material can do the job,” he said. “It's all about gathering data. Penn State Harrisburg has been an invaluable asset.”

While reclaimed sands meet standards for masonry blocks, the sands currently do not meet all of the requirements to be used in concrete. During cement processing, aluminum within the ash aggregate produces hydrogen gas that becomes trapped in the concrete and reduces its structural capacity. Masonry blocks are subjected to minimal hydrogen gas effects. Mathews is working with a colleague in chemical engineering, Faeghen Moazeni, to test pre-treatment solutions of the reclaimed sands to be used in concrete and has applied for a grant to further these treatment studies.

Perfecting the process to meet specifications for concrete could help buildings meet Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification for sustainability, Mathews said.

“Engineers have a responsibility to use materials that are safe and sustainable. We shouldn't always do the same old thing. I want to do something that has real impact,” he said.

Student's background in concrete provides foundation for research connections

Michael Young, one of Mathews' graduate students, has a background different from most other students. He owned his own concrete construction company for 30 years before deciding to go back to school to get his engineering degree. He earned his bachelor of science in civil engineering from Penn State Harrisburg in 2017 and now is pursuing graduate study with a focus on materials.

He said he decided to go back to school when he began to have his own limitations with the physical demands of working with heavy concrete.

“You pick things up. Life experience has value,” Young, 51, said. “The hardest thing [about returning to school] was the studying part. When you're younger, your memory is better.”

At Penn State Harrisburg, he has enjoyed working with the younger students for their willingness to learn and their enthusiasm about environmental sustainability, he said.

Young’s professional experience has been a driving force in making the connections for ongoing research into incinerator ash recycling, helping to secure support for the project.

Young believes that continuing to work with the incinerator ash will turn into his next career. That's why he thinks working in the Penn State Harrisburg materials lab is important.

Mathews said Young's college path “showcases the benefits of coming back to school for professionals with several years of workforce experience.”

“Through both his classwork and his research studies, Michael has shown how his years of experience and extensive industry connections can enhance classroom education and research,” Mathews said.