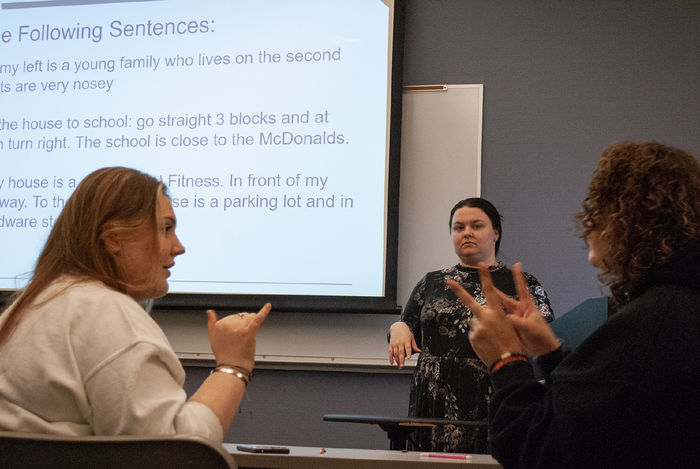

Students practice signs during American Sign Language II in spring 2024. Penn State Harrisburg offers American Sign Language I and II.

MIDDLETOWN, Pa. — In a quiet Madlyn Hanes Library classroom last spring, a handful of students watched as American Sign Language (ASL) II instructor Ellen Delp pointed to pictures on a big screen, then demonstrated the hand motions to say the words in sign language.

She and the students don’t speak out loud. Questions, if they can’t be signed, are tapped out on phones and answers demonstrated, or occasionally written on the white board.

“I expect them not to talk and I don’t talk either,” Delp, affiliate instructor in audiology and otolaryngology, said. “I really want them to have an immersive experience.”

Penn State Harrisburg offers American Sign Language I and II, and interest in the classes is expected to increase as the college’s communication sciences and disorders program, which began in 2020, grows.

At Harrisburg, the courses have drawn students from a variety of majors, including communication sciences and disorders, but also psychology, cyber security and more, Delp said. Her most recent ASL II course included a student who is studying special education at a different nearby university, where ASL isn’t currently offered.

Delp said she thinks there is more general interest in the course.

One of the first homework pieces she assigns in her ASL I course asks the students why they are interested in studying sign language. Many have an interest in communicating with individuals or family members who are deaf. Some want to learn the skill for their jobs; one just wanted to be better able to communicate with their nonverbal child.

Delp said the courses cover basic everyday conversation and survival skills — how to talk about school, family, travel and how to ask for signs or for information.

“We do cover a little of Deaf culture,” Delp said, adding that she adjusts how much depending on whether students are planning to take Penn State Harrisburg’s separate Deaf culture course. “It’s different than a spoken language. I have to teach them how to get a person’s attention. We have to do very basic stuff [such as] how to address people or how to walk through two people who are signing.”

After the first day, Delp requires her class to be “voices off.” If students have questions or comments that they cannot yet sign, they can write her notes using paper or their phones.

“There is a lot of value to having a deaf ASL teacher,” Delp said. “I try to emulate that even though I’m not deaf.”

Some students said it took a little time to get used to not speaking during class, but it was also a way of being respectful to the Deaf community. Others said it was necessary for what they were learning.

“It’s important because it’s not a spoken language,” said psychology major Sophia Gomez. “Being able to immerse ourselves totally helps us learn it.”

Mackenzie Phillips said she wants to work with children who have special needs, and ASL can be an easier form of communication for some.

“I find it to be beneficial working on campus with students with intellectual disabilities,” said Phillips, who works as a peer mentor for students with intellectual disabilities through the Career Studies program.

Communication Sciences and Disorders major Tressa Burger, who is also a peer mentor, said she wants to one day be an ENT (ear, nose and throat specialist) specializing in hearing.

“ASL has helped me to become more aware and sensitive towards the Deaf community,” she said. “Since I may be working with members of the Deaf community, it is crucial to be understanding of their culture. Learning ASL has also helped me develop communication skills that will hopefully allow me to better communicate with deaf patients I may have.”