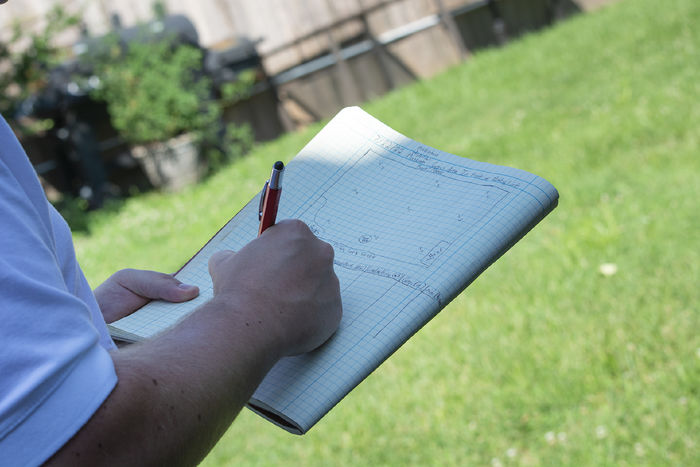

Travis Peters, front, a recent Penn State graduate, and Jonathan Fischer, a Penn State Harrisburg student, use equipment in the yard of the Middletown Area Historical Society in July 2022 to gather data on how much water the soil can store.

MIDDLETOWN, Pa. — Last summer, on a sweltering July morning, Penn State Harrisburg environmental engineering professor Shirley Clark and two students worked in the yard of the Middletown Area Historical Society on East Main Street.

Using equipment — moisture sensors, compaction meters and infiltrometers — they gathered data to help them learn more about how much water the soil can store when it rains and how the water moves below the surface of the soil.

The data could help better explain flash flooding that Middletown experiences. But since the data alone can’t explain the impact flooding has on the community and people who live there, Clark is teaming up with ethnographers from the college’s School of Humanities.

Through a $120,000 Pennsylvania Sea Grant, Clark, along with Anthony Buccitelli, associate professor of American studies and communications, and Jeffrey Tolbert, assistant professor of American studies and folklore, are pursuing an interdisciplinary research project combining engineering and ethnography to examine flooding in the Middletown community.

Together they seek to gain a better understanding of stormwater flow, buried streams and shallow groundwater in the borough as well as the impact that storms and flooding have on the community — and how better design could help prevent negative impacts in the future.

“The storms we were designing for are changing — these big intense storms,” Clark said. “I hope we can continue to improve and better inform what’s going on.”

Robin Pellegrini, a trustee for the Middletown Area Historical Society, watched last July as Clark and two students took measurements. She said she was excited that Penn State Harrisburg received the grant, noting that understanding prior history can help prevent future problems.

Measuring flooding

In recent years, Middletown has experienced intense storms that have caused flash flooding in areas not identified as FEMA flood plains, according to the research team. A summer 2017 storm dropped 4.7 inches on Middletown borough in just less than an hour and a half.

Street flooding tends to occur in the center of the borough, indicating that the storm sewer cannot contain such severe storms, Clark said, and residents have noted water bubbling up in their basements during heavy rain, an indication of shallow groundwater.

In addition to being an environmental engineering professor, Clark is a Middletown resident and a history buff. She found that maps of the borough from 1862 show streams that are no longer on the surface of the land today, because they were buried underground many years ago to make way for development. One of those streams, called Bloody Run, goes directly under the center of town.

That means now, the piping system is not only carrying storm flows but the stream as well, and that needs to be accounted for in stormwater design, Clark said.

“What we’re trying to do is better understand how things are developed and how this impacts what goes in that pipe and how often that pipe is inundated,” she said.

The data collected from the Middletown Historical Society yard is helping to do that.

“It’s actually helping us understand how much water the soil can store during a storm and also helps us understand, given changes in that depth, how water is moving laterally just below the soil surface,” Clark said.

Clark and her team have taken similar samples in additional locations and also installed long-term sensors in two locations — near the old water treatment plant on Mill Street as well as in Oak Hills Park.

In both of those spots, they installed sensors stacked on top of each other: one about 3.5 inches deep in the ground, and the other about 7 or 8 inches deep.

At the water treatment plant site, Clark's team found what looked like a layer of clay, where the soil is compacted, between those two depths. The soil at the park site, where there’s been no development, did not have such a layer.

Those sensors are showing that it takes less time — about 10-15 minutes — for the water to seep to the deeper sensor in the park. It takes longer for the water to reach the same depth — if it ever does — near the old treatment plant.

“What that tells us is that compaction layer is effectively acting like a bowl and holding onto the water,” Clark said. “So effectively what we’re getting is not much soil storage — which means we get more runoff, more flooding.”

Determining just how shallow that bowl is could help engineers who are doing any kind of site design — commercial, residential or otherwise — to design correctly.

Community impact

A team from the School of Humanities is studying a similar set of questions as Clark, but from a sociocultural perspective, according to Buccitelli.

Buccitelli said they are interested in three areas: understanding and documenting narratives about floods; building a folk geography of the area, documenting places considered significant or places people attach memories; and learning more about how people think, broadly, about relationship between themselves and the community and the natural environment.

For example, he said, the dollar value of a box destroyed by a flood is probably minimal. But if it was a box of photographs, the personal, family or community impact would be much more significant.

Often, the storms causing flooding in Middletown don’t rise to the level that they bring in disaster aid, so there can be significant economic impacts as well. Buccitelli said that in addition to recording the human-level impact, the team is looking to differentiate the impacts among different social groups.

“What we’re aiming to do is drill down a little bit more to understand how these kinds of events might impact different segments of the community in much different ways,” Buccitelli said.

To do that, graduate student Stephen Lochetto has been making his way around the Middletown community, gathering stories of flooding.

On a rainy spring morning, Lochetto stood in the basement of the B’nai Jacob Synagogue in Middletown, where Larry Kapenstein, the synagogue’s treasurer and shamash, told him about the water that repeatedly creeped up through the floor in the past 15 years or so.

More than one person stepped right through the floor, and the large safe that holds the synagogue’s Torahs had begun to sink. After many attempts at temporary fixes, the synagogue raised more than $50,000 to make major, permanent repairs.

As they talked, Kapenstein mentioned that his wife had grown up in Middletown and lived there during Hurricane Agnes, and her father had been mayor of town. Soon Lochetto was making plans to connect with Kapenstein’s family.

That’s how he has spent much of the past two semesters — collecting stories and memories of flooding from residents, with one connection often leading to another.

Lochetto is studying for his doctoral degree in American studies, but his background is in biology, he said.

“I think interdisciplinary projects are great, and unfortunately you don’t see a lot of them,” Lochetto said. “It shows you can use both aspects of academia to really look into a problem really well.”

The scientific angle provides data, he said. The ethnography aspect provides what people on the ground are really saying and thinking.

“This combined approach is really powerful,” said Lochetto. “Ethnography and engineering can really complement each other.”

Impact beyond Middletown

Clark plans to share whatever her team discovers with Middletown borough or with the state officials who are rewriting a state stormwater design manual.

The researchers are also working to extend their research beyond Middletown and to create a Penn State Harrisburg research group around environmental issues from multiple perspectives.

Clark is part of a Penn State team on a Department of Energy-funded Urban Integrated Field Lab project, where she is heading an urban hydrology section and hopes to apply the Middletown research in Baltimore, she said. Additional grant funds are also being sought to expand the work.

Buccitelli said the project is the kind of work that desperately needs to be done, in areas across the United States as well as the world.

“[Bringing together] anthropologists, folklorists and humanistic social scientists with folks who are doing this kind of environmental impact work will produce a much richer set of data that we can work from to try to improve both humanistic and environmental outcomes,” Buccitelli said.