Autism should be treated according to proven scientific approaches, say Penn State Harrisburg researchers.

MIDDLETOWN, Pa. -- Kimberly Schreck has met families who spent thousands of dollars, even remortgaged their homes, to pay for unproven treatments to try to help their autistic children.

Desperate parents sometimes will try almost anything.

"As a mom, I get that," says Schreck, professor of psychology at Penn State Harrisburg.

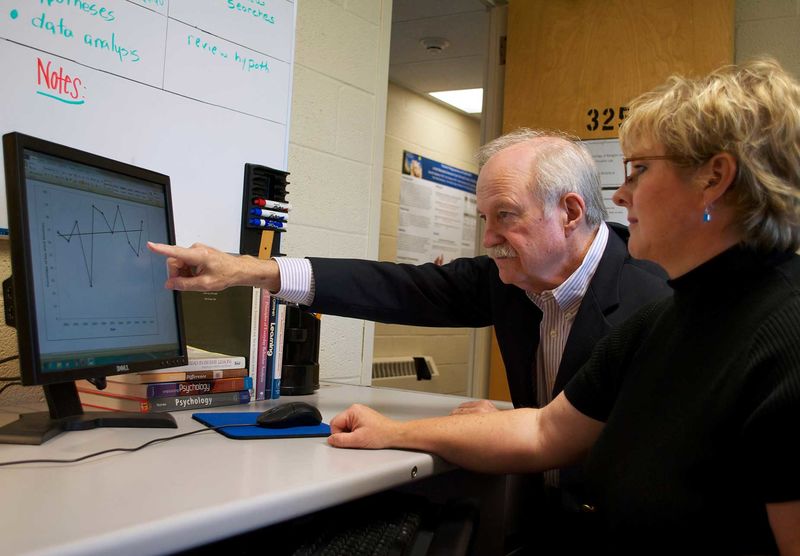

She and her colleague, Professor of Psychology Richard Foxx, are helping families cut through the hype and zero in on the most effective treatments to help children with autism. They want to save families time, money and disappointment.

Autism is a confusing range of complex neurodevelopment disorders characterized by social impairments, communication difficulties and repetitive behaviors. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that one in 88 children has been identified with autism spectrum disorder. Boys are four times more likely than girls to have some form of autism.

"They're such perplexing children," Foxx says. "They may show these splinter skills [skills mastered well ahead of a child's usual developmental sequence], which makes it difficult for parents. It's maddening."

Foxx and Schreck conduct research on successful methods for treating autism. They've seen plenty of unproven, ineffective methods over the years. Foxx calls them "fad treatments," cautioning that practitioners give parents false hope with no clinical proof to back up their claims. Schreck labels them "junk science."

"Some are out for money," she says. "Others really do care about the children, but they're not testing whether what they are doing works."

While some doctors tell parents that alternative treatments can't hurt, Schreck disagrees. A child with autism may need as much as 40 hours of effective behavioral services a week, she explains. When a family's weekly involvement in seeking treatment includes four hours of massage therapy, six hours of sitting with head phones on listening to random sounds and two hours having the child's urine analyzed, valuable time is lost for methods that actually work.

Schreck and Foxx steer families toward applied behavior analysis (ABA), which teaches behaviors through a system of rewards and consequences. The National Institutes of Mental Health, the Surgeon General and the American Academy of Pediatrics have endorsed ABA as the clinical standard-of-care treatment for autism.

Applied behavior analysis is based on more than 40 years of research and experimentation with people and animals, using scientifically based principles of learning that apply to everyone. It focuses on principles that explain how learning takes place -- what causes a new behavior to be learned or an old one to be changed. This information can be used to motivate everyone from disruptive fourth graders to business executives to learn to behave in ways that benefit them.

Positive reinforcement is one such principle. When a behavior is followed by a reward, the behavior is more likely to be repeated.

These principles work with any group of people, according to Foxx, whose research has illustrated the wide application of behavior analysis and who recently received the American Psychological Association Award for Distinguished Professional Contributions to Applied Research. For example, Foxx worked with an airline that sought to use behavioral methods to increase workers' safety habits on the flight line. ABA principles are also behind the techniques Foxx and co-author Nathan Airing recommend in their best-selling book, Toilet Training in Less Than a Day.

ABA uses reinforcement to help autistic children in every portion of their lives, having been shown to significantly improve communication, social relationships, play, self-care and school success as well as reduce problem behaviors such as self-injury and aggression. It means people can live more normal lives -- visiting restaurants or going on vacation -- once the child learns how to behave in those situations.

Unfortunately, unproven autism treatments like vitamin therapy or facilitated communication get too much press attention in U.S. newspapers and magazines, Schreck notes. She recently began analyzing television coverage as well, looking at how many times the media talks about treatments and the number of positive and negative comments. Parents even get recommendations for less reputable treatment methods from teachers, pediatricians, human services professionals and other parents, she says.

Schreck and graduate student Brenda McCants are studying fad treatments from as far back as the 1800s, evaluating how they change over time. When a method stopped making money or hit a legal obstacle, practitioners would change the product name or change who they targeted. The fads did not disappear; they evolved.

With the explosion in numbers of children being diagnosed with autism, Schreck is seeing the number of opportunists balloon.

"We don't want to confront," she emphasizes. "We just want to get the word out: ABA is the way to go. Science is the way to go."

Kimberley A. Schreck and Richard M. Foxx are both professors of psychology at Penn State Harrisburg.

This story is abridged from an article in Penn State Harrisburg Currents. The full story is on the Penn State Harrisburg website.